There is a long list of factors accelerating climate change and loss of biodiversity. Among the loss in biodiversity are the pollinators that keep food systems fruitful. The decline in pollinators is an alarming ecological and economical problem. Roughly $235-577 billion dollars of annual global food production relies on pollinators. In 2012, gross revenue from US pollination services was estimated at $656 million. There is a lot of research being done by governments, universities and non-profit organizations using social bees as model species to understand the decline in pollinators. Social bees like honeybees and bumblebees may not be the best model as they only represent a small portion of bees. Solitary bees make up roughly 90% of all bees with over 20,000 different species.

Solitary Bee Life-cycle

Did you know that one solitary bee can do the work of up to 60 honeybees? Solitary bee nests lack large populations and the division of labor found in honeybee colonies. The adult female solitary bee is the ultimate homemaker, performing every task in the nest by herself.

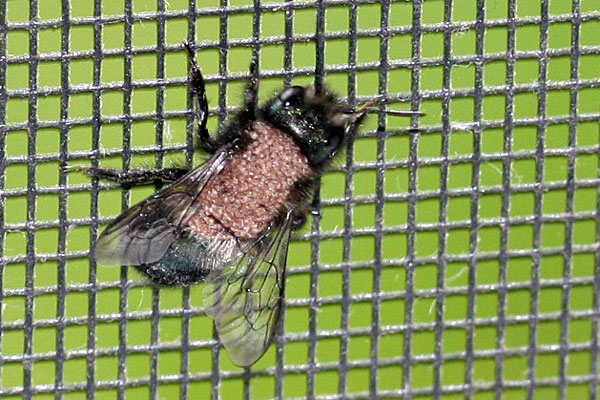

Adults emerge at different times in the spring and summer depending on when their primary floral source becomes available. Males always emerge first, protecting nearby pollen and nectar sources from competing pollinators while waiting for a mate. Like honeybees, males die soon after mating while the female will begin establishing her nest and foraging for pollen and nectar. The pollen does not form into baskets on her legs like honeybees, rather she has specialized hairs (scopa) on her abdomen and legs to accumulate large amounts of pollen. She deposits pollen into tunnels in her nest, turning it into “bee butter” by regurgitating nectar on the pollen to form a ball. She lays a single egg in the bee butter after enough resources are accumulated to sustain a new bee until full maturity. She then seals the first completed brood chamber and begins developing new chambers. A female solitary bee lays only a few dozen eggs in her lifetime. In comparison, queen bees can lay up to 3000 eggs a day! Eggs will hatch into developing larvae, the larvae will consume the pollen ball before spinning a cocoons to overwinter in before emerging as adults the following spring/summer.

What’s threatening Solitary Bees?

Colony loss, viruses and diseases are well documented in social bees. You’ve likely heard of Varroa destructor which transmits viruses like Deformed Wing Virus and the numerous bacterial and fungal diseases that infect brood like Nosema, European Foulbrood and Chalkbrood. Honeybee diseases are also being transferred to bumblebees. Black Queen Cell Virus (BQCV), Deformed Wing Virus, Acute Bee Paralysis Virus, Slow Bee Paralysis Virus and Nosema ceranae are now found in bumblebee populations that share resources with managed honeybee colonies.

In the absence of nurse bees to remove diseased brood, solitary bee brood may be more susceptible to pathogens. The fungal disease Chalkbrood also infects solitary bee brood. Pests also threaten solitary bees. The pollen mite (Chaetodactylus) enters the nest on the thorax of solitary bees where it reproduces and feeds on bee butter. With enough mite pressure, the young solitary bee larvae can starve to death. Brood not immediately killed by the mites directly or from starvation, will emerge as adults with an infestation of new mites in the spring. Both diseases and mites can continue to infect solitary bees that reuse infected nesting sites.

Save the bees, all of them!

Aside from pests and pathogens, a lot of research now focuses on the role microbes play in honeybee health and nutrition. Microbes break down complex carbohydrates and protein into easy to digest molecules and help bolster the immune system to inhibit pathogen proliferation. Honeybees accumulate their gut biome through direct social and environmental contact. Since the gut biome is influenced by the hive, honeybees have a fairly stable microbial community. Solitary bees rely strictly on environmental transmission pathways and therefore the gut community fluctuates based on the health of plants and their pollen-borne microbial symbionts. Lactobacillus species play a vital role in the nutrition and immunity of honeybees and solitary bees. Fortunately, many probiotic products are now on the market that are meant to support the health of honeybees with lactic acid producing bacteria as a main component. Since solitary bees are also a managed bee species, it would be interesting to see if probiotics provide the same benefits. Aside from supplements to help the bees from disease, reducing the long list of factors that contribute to climate change and the loss of biodiversity can also make a large positive impact on pollinators.

Native pollinators like solitary bees are just as important as honeybees. With habitat loss contributing to pollinator decline, it is important to find ways to help all the bees. Just as beekeepers set up ideal conditions to collect honeybee swarms, beekeepers and non-beekeepers alike can set up conditions to support native pollinators. Whether that be planting flowers, building bee nests or refraining from using pesticides on your lawn – we all can serve an important role in saving our pollinators.